This article is designed to be an easy-to-understand guide on what happens now that the UK has voted to leave the European Union.

- 1 What does Brexit mean?

- 2 Why is Britain leaving the European Union?

- 3 What was the breakdown across the UK?

- 4 What has happened since the referendum?

- 5 What about the economy?

- 6 What is the European Union?

- 7 So when will Britain actually leave it?

- 8 What about the court challenge to the Brexit process?

- 9 Who is going to negotiate Britain’s exit from the EU?

- 10 How long will it take for Britain to leave the EU?

- 11 Why will Brexit take so long?

- 12 The likely focus of negotiations between the UK and EU

- 13 What do “soft” and “hard” Brexit mean?

- 14 What happens to EU citizens living in the UK?

- 15 What happens to UK citizens working in the EU?

- 16 What about EU nationals who want to work in the UK?

- 17 What does the fall in the value of the pound mean for prices in the shops?

- 18 Will immigration be cut?

- 19 Could there be a second referendum?

- 20 Will MPs get a vote on the Brexit deal?

- 21 Will I need a visa to travel to the EU?

- 22 Will I still be able to use my passport?

- 23 Some say we could still remain in the single market – but what is a single market?

- 24 Has any other member state ever left the EU?

- 25 What does this mean for Scotland?

- 26 What does it mean for Northern Ireland?

- 27 How will pensions, savings, investments and mortgages be affected?

- 28 Will duty-free sales on Europe journeys return?

- 29 Will EHIC cards still be valid?

- 30 Will cars need new number plates?

- 31 Could MPs block an EU exit?

- 32 Will leaving the EU mean we don’t have to abide by the European Court of Human Rights?

- 33 Will the UK be able to rejoin the EU in the future?

- 34 Who wanted the UK to leave the EU?

- 35 What were their reasons for wanting the UK to leave?

- 36 Who wanted the UK to stay in the EU?

- 37 What were their reasons for wanting the UK to stay?

- 38 What about businesses?

- 39 Who led the rival sides in the campaign?

- 40 Will the EU still use English?

- 41 Will a Brexit harm product safety?

- 42 Which MPs were for staying and which for leaving?

- 43 How much does the UK contribute to the EU and how much do we get in return?

- 44 If I retire to Spain or another EU country will my healthcare costs still be covered?

- 45 What will happen to protected species?

- 46 How much money will the UK save through changes to migrant child benefits and welfare payments?

- 47 Will we be barred from the Eurovision Song Contest?

- 48 Has Brexit made house prices fall?

- 49 What is the ‘red tape’ that opponents of the EU complain about?

- 50 Will Britain be party to the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership?

- 51 What impact will leaving the EU have on the NHS?

What does Brexit mean?

It is a word that has become used as a shorthand way of saying the UK leaving the EU – merging the words Britain and exit to get Brexit, in a same way as a possible Greek exit from the euro was dubbed Grexit in the past.

Why is Britain leaving the European Union?

A referendum – a vote in which everyone (or nearly everyone) of voting age can take part – was held on Thursday 23 June, to decide whether the UK should leave or remain in the European Union. Leave won by 52% to 48%. The referendum turnout was 71.8%, with more than 30 million people voting.

What was the breakdown across the UK?

England voted for Brexit, by 53.4% to 46.6%, as did Wales, with Leave getting 52.5% of the vote and Remain 47.5%. Scotland and Northern Ireland both backed staying in the EU. Scotland backed Remain by 62% to 38%, while 55.8% in Northern Ireland voted Remain and 44.2% Leave. See the results in more detail.

What has happened since the referendum?

Britain has got a new Prime Minister – Theresa May. The former home secretary took over from David Cameron, who resigned on the day after losing the referendum.

Like Mr Cameron, Mrs May was against Britain leaving the EU but she says she will respect the will of the people. She has said “Brexit means Brexit” but there is still a lot of debate about what that will mean in practice especially on the two key issues of how British firms do business in the European Union and what curbs are brought in on the rights of European Union nationals to live and work in the UK.

What about the economy?

The UK economy appears to have weathered the initial shock of the Brexit vote, although the value of the pound remains near a 30-year low, but opinion is sharply divided over the long-term effects of leaving the EU. Some major firms such as Easyjet and John Lewis have pointed out that the slump in sterling has increased their costs.

Britain also lost its top AAA credit rating, meaning the cost of government borrowing will be higher. But share prices have recovered from a dramatic slump in value, with both the FTSE 100 and the broader FTSE 250 index, which includes more British-based businesses, trading higher than before the referendum.

The Bank of England is hoping its decision to cut interest rates from 0.5% to 0.25% – a record low and the first cut since 2009 – will stave off recession and stimulate investment, with some economic indicators pointing to a downturn.

Here is a detailed rundown of how Britain’s economy is doing

What is the European Union?

The European Union – often known as the EU – is an economic and political partnership involving 28 European countries (click here if you want to see the full list). It began after World War Two to foster economic co-operation, with the idea that countries which trade together are more likely to avoid going to war with each other.

It has since grown to become a “single market” allowing goods and people to move around, basically as if the member states were one country. It has its own currency, the euro, which is used by 19 of the member countries, its own parliament and it now sets rules in a wide range of areas – including on the environment, transport, consumer rights and even things such as mobile phone charges. Click here for a beginners’ guide to how the EU works.

So when will Britain actually leave it?

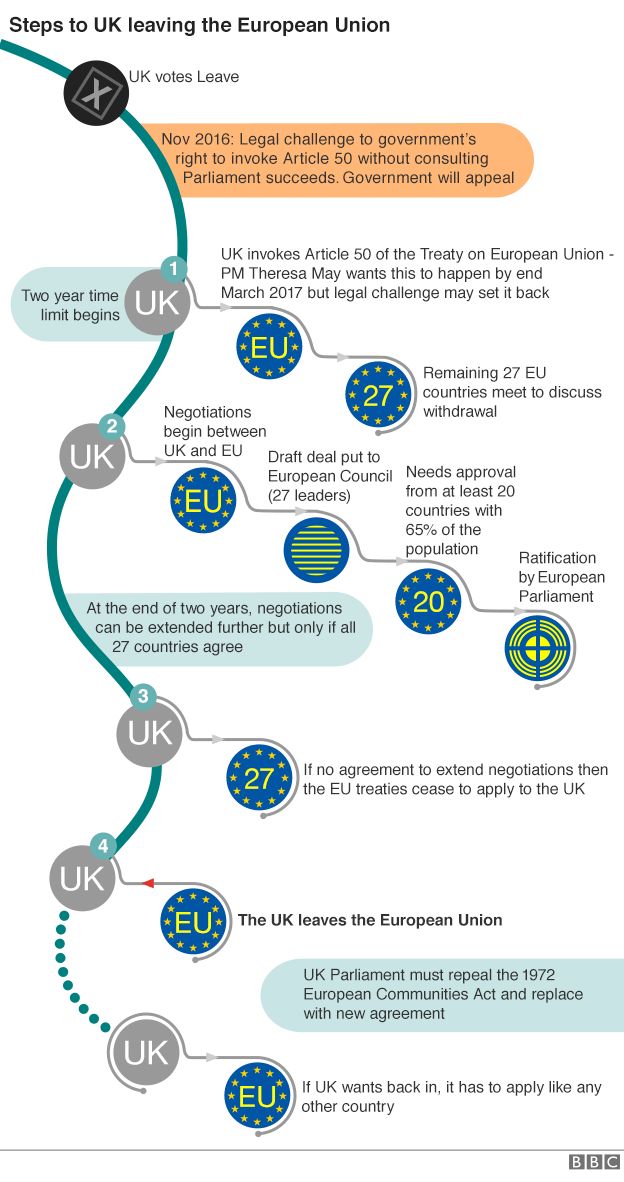

For the UK to leave the EU it has to invoke an agreement called Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty which gives the two sides two years to agree the terms of the split. Theresa May has said she intends to trigger this process by the end of March 2017, meaning the UK will be expected to have left by the summer of 2019, depending on the precise timetable agreed during the negotiations.

Once negotiations officially begin, we will start to get a clear idea of what kind of deal the UK will seek from the EU, on trade and immigration.

The government will also enact a Great Repeal Bill which will end the primacy of EU law in the UK. It is expected to incorporate all EU legislation into UK law in one lump, after which the government will decide over a period of time, which parts to keep, change or retain.

What about the court challenge to the Brexit process?

A court challenge to Theresa May’s right to trigger the Article 50 process without getting the backing of Parliament was successful in the High Court. Downing Street has since appealed to the Supreme Court with a judgement expected in January.

Downing Street says it intends to stick to its March timetable for the beginning of the two year exit talks. Even if the government’s appeal fails it does not mean necessarily that there will be any delays to Brexit. It is expected that in those circumstances usual business might be cleared so a very short Act of Parliament could be brought forward to go through the Commons and Lords.

Although it is generally believed that the go-ahead would ultimately be given – because most MPs have said they would respect the EU referendum result – having to go through the full parliamentary process could prompt attempts to amend the legislation or add in caveats, such as the UK having to negotiate a deal which included staying the European single market after Brexit. Read a simple key points guide to the Supreme Court case.

Who is going to negotiate Britain’s exit from the EU?

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES

Image copyright GETTY IMAGESTheresa May set up a government department, headed by veteran Conservative MP and Leave campaigner David Davis, to take responsibility for Brexit. Former defence secretary, Liam Fox, who also campaigned to leave the EU, was given the new job of international trade secretary and Boris Johnson, who was a leader of the official Leave campaign, is foreign secretary.

These men – dubbed the Three Brexiteers – will play a central role in negotiations with the EU and seek out new international agreements, although it will be Mrs May, as prime minister, who will have the final say. The government did not do any emergency planning for Brexit ahead of the referendum and Mrs May has rejected calls to say what her negotiating goals are.

How long will it take for Britain to leave the EU?

Once Article 50 has been triggered, the UK will have two years to negotiate its withdrawal. But no one really knows how the Brexit process will work – Article 50 was only created in late 2009 and it has never been used.

Former Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond, now Chancellor, wanted Britain to remain in the EU, and he has suggested it could take up to six years for the UK to complete exit negotiations. The terms of Britain’s exit will have to be agreed by 27 national parliaments, a process which could take some years, he has argued.

EU law still stands in the UK until it ceases being a member. The UK will continue to abide by EU treaties and laws, but not take part in any decision-making.

Why will Brexit take so long?

Unpicking 43 years of treaties and agreements covering thousands of different subjects was never going to be a straightforward task. It is further complicated by the fact that it has never been done before and negotiators will, to some extent, be making it up as they go along.

The post-Brexit trade deal is likely to be the most complex part of the negotiation because it needs the unanimous approval of more than 30 national and regional parliaments across Europe, some of whom may want to hold referendums.

The likely focus of negotiations between the UK and EU

In very simplified terms, the starting positions are that the EU will only allow the UK to be part of the European single market (which allows tariff-free trade) if it continues to allow EU nationals the unchecked right to live and work in the UK. The UK says it wants controls “on the numbers of people who come to Britain from Europe”. Both sides want trade to continue after Brexit with the UK seeking a positive outcome for those who wish to trade goods and services” – such as those in the City of London. The challenge for the UK’s Brexit talks will be to do enough to tackle immigration concerns while getting the best possible trade arrangements with the EU.

Some Brexiteers, such as ex-chancellor Lord Lawson, say that as the UK does not want freedom of movement and the EU says that without it there is no single market membership, the UK should end “uncertainty” by pushing ahead with Brexit and not “waste time” trying to negotiate a special deal.

What do “soft” and “hard” Brexit mean?

These terms are increasingly being used as debate focuses on the terms of the UK’s departure from the EU. There is no strict definition of either, but they are used to refer to the closeness of the UK’s relationship with the EU post-Brexit.

So at one extreme, “hard” Brexit could involve the UK refusing to compromise on issues like the free movement of people in order to maintain access to the EU single market. At the other end of the scale, a “soft” Brexit might follow a similar path to Norway, which is a member of the single market and has to accept the free movement of people as a result.

Ex-chancellor George Osborne and Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn are among those to have warned against pursuing a “hard” option, while some Eurosceptic Conservative MPs have put forward the opposite view.

What happens to EU citizens living in the UK?

The government has declined to give a firm guarantee about the status of EU nationals currently living in the UK, saying this is not possible without a reciprocal pledge from other EU members about the millions of British nationals living on the continent.

EU nationals with a right to permanent residence, which is granted after they have lived in the UK for five years, will be be able to stay, the chief civil servant at the Home Office has said. The rights of other EU nationals would be subject to negotiations on Brexit and the “will of Parliament”, he added.

What happens to UK citizens working in the EU?

A lot depends on the kind of deal the UK agrees with the EU. If it remains within the single market, it would almost certainly retain free movement rights, allowing UK citizens to work in the EU and vice versa. If the government opted to impose work permit restrictions, then other countries could reciprocate, meaning Britons would have to apply for visas to work.

What about EU nationals who want to work in the UK?

Again, it depends on whether the UK government decides to introduce a work permit system of the kind that currently applies to non-EU citizens, limiting entry to skilled workers in professions where there are shortages.

Citizens’ Advice has reminded people their rights have not changed yet and asked anyone to contact them if they think they have been discriminated against following the Leave vote.

Brexit Secretary David Davis has suggested EU migrants who come to the UK as Brexit nears may not be given the right to stay. He has said there might have to be a cut-off point if there was a “surge” in new arrivals.

What does the fall in the value of the pound mean for prices in the shops?

People travelling overseas from the UK have found their pounds are buying fewer euros or dollars after the Brexit vote.

The day-to-day spending impact is likely to be more significant. Even if the pound regains some of its value, currency experts expect it to remain at least 10% below where it was on 23 June, in the long term.

This means imported goods will consequently get more expensive – some price rises for food, clothing and homeware goods have already been seen and the issue was most notably illustrated by the dispute between Tesco and Marmite’s makers about whether prices would be put up or not in the stores.

However the current UK inflation rate is 1% so it remains to be seen how big an effect currency fluctuations have in the longer term.

Will immigration be cut?

Image copyright PA

Image copyright PAPrime Minister Theresa May has said one of the main messages she has taken from the Leave vote is that the British people want to see a reduction in immigration.

She has said this will be a focus of Brexit negotiations. As mentioned above, the key issue is whether other EU nations will grant the UK access to the single market, if that is what it wants, while at the same time being allowed to restrict the rights of EU citizens to live and work in the UK.

Mrs May has said she remains committed to getting net migration – the difference between the numbers entering and leaving the country – down to a “sustainable” level, which she defines as being below 100,000 a year. It is currently running at 330,000 a year, of which 184,000 are EU citizens, and 188,000 are from outside the EU – the figures include a 39,000 outflow of UK citizens.

Could there be a second referendum?

It seems highly unlikely. Both the Conservatives and the Labour Party have ruled out another referendum, arguing that it would be an undemocratic breach of trust with the British people who clearly voted to Leave. The Liberal Democrats – who have just a handful of MPs – have vowed to halt Brexit and keep Britain in the EU if they were to win the next general election.

Some commentators, including former House of Commons clerk Lord Lisvane, have argued that a further referendum would be needed to ratify whatever deal the UK hammers out with the EU, but there are few signs political leaders view this as a viable option.

Will MPs get a vote on the Brexit deal?

Yes. Theresa May has appeared keen to avoid a vote on her negotiating stance, to avoid having to give away her priorities, but it has seemed clear there will be a Commons vote to approve whatever deal the UK and the rest of the EU agree at the end of the two year process. It is worth mentioning that it looks like the deal also has to be agreed by the European Parliament – with British MEPs getting a chance to vote on it there.

Will I need a visa to travel to the EU?

While there could be limitations on British nationals’ ability to live and work in EU countries, it seems unlikely they would want to deter tourists. There are many countries outside the European Economic Area, which includes the 28 EU nations plus Iceland, Lichtenstein and Norway, that British citizens can visit for up to 90 days without needing a visa and it is possible that such arrangements could be negotiated with European countries.

Image copyright REUTERS

Image copyright REUTERSWill I still be able to use my passport?

Yes. It is a British document – there is no such thing as an EU passport, so your passport will stay the same. In theory, the government could, if it wanted, decide to change the colour, which is currently standardised for EU countries, says the BBC’s Europe correspondent, Chris Morris.

Some say we could still remain in the single market – but what is a single market?

The single market is seen by its advocates as the EU’s biggest achievement and one of the main reasons it was set up in the first place.

Britain was a member of a free trade area in Europe before it joined what was then known as the common market. In a free trade area countries can trade with each other without paying tariffs – but it is not a single market because the member states do not have to merge their economies together.

The European Union single market, which was completed in 1992, allows the free movement of goods, services, money and people within the European Union, as if it was a single country.

It is possible to set up a business or take a job anywhere within it. The idea was to boost trade, create jobs and lower prices. But it requires common law-making to ensure products are made to the same technical standards and imposes other rules to ensure a “level playing field”.

Critics say it generates too many petty regulations and robs members of control over their own affairs. Mass migration from poorer to richer countries has also raised questions about the free movement rule. Read more: A free trade area v EU single market

Has any other member state ever left the EU?

No nation state has ever left the EU. But Greenland, one of Denmark’s overseas territories, held a referendum in 1982, after gaining a greater degree of self government, and voted by 52% to 48% to leave, which it duly did after a period of negotiation. The BBC’s Carolyn Quinn visited Greenland at the end of last year to find out how they did it.

Image copyright REUTERS

Image copyright REUTERSWhat does this mean for Scotland?

Scotland’s First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said in the wake of the Leave result that it is “democratically unacceptable” that Scotland faces being taken out of the EU when it voted to Remain. A second independence referendum for the country is now “highly likely”, she has said.

What does it mean for Northern Ireland?

Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness said the impact in Northern Ireland would be “very profound” and that the whole island of Ireland should now be able to vote on reunification. But, speaking while she was still Northern Ireland Secretary, Theresa Villiers ruled out the call from Sinn Féin for a border poll, saying the circumstances in which one would be called did not exist.

How will pensions, savings, investments and mortgages be affected?

During the referendum campaign, David Cameron said the so-called “triple lock” for state pensions would be threatened by a UK exit. This is the agreement by which pensions increase by at least the level of earnings, inflation or 2.5% every year – whichever is the highest.

If economic performance deteriorates, the Bank of England could decide on a further programme of quantitative easing, as an alternative to cutting interest rates, which would lower bond yields and with them annuity rates. So anyone taking out a pension annuity could get less income for their money. Though it’s worth pointing out that annuity rates have been falling since before the vote anyway.

The Bank of England may consider raising interest rates to combat extra pressure on inflation. That would make mortgages and loans more expensive to repay but would be good news for savers. However it is still too soon to say whether or not these warnings will prove accurate.

Will duty-free sales on Europe journeys return?

Image copyright THINKSTOCK

Image copyright THINKSTOCKJournalists and writers on social media have greeted the reintroduction of duty-free sales as an “upside” or “silver lining” of Brexit. As with most Brexit consequences, whether this will happen depends on how negotiations with the EU play out – whether the “customs union” agreement between Britain and the EU is ended or continued.

Eurotunnel boss Jacques Gounon said last November the reintroduction of duty-free would be “an incredible boost for my business” but he later said that remark had been “light-hearted”. Erik Juul-Mortensen, president of the Tax Free World Association (TFWA) said after the referendum vote “it is not possible to predict how Brexit will affect the duty free and travel retail industry, and it is wiser not to make assumptions about exactly what the impact will be.”

Will EHIC cards still be valid?

They are at the moment but no-one knows the longer term prospects for definite. The EHIC card – which entitles travellers to state-provided medical help for any condition or injury that requires urgent treatment, in any other country within the EU, as well as several non-EU countries – is not an EU initiative. It was negotiated between countries within a group known as the European Economic Area, often simply referred to as the single market (plus Switzerland, which confusingly is not a member of the EEA, but has agreed access to the single market). Therefore, the future of Britons’ EHIC cover could depend on whether the UK decided to sever ties with the EEA.

Will cars need new number plates?

Probably not, says BBC Europe correspondent Chris Morris, because there’s no EU-wide law on vehicle registration or car number places, and the EU flag symbol is a voluntary identifier and not compulsory. The DVLA says there has been no discussion about what would happen to plates with the flag if the UK voted to leave.

Could MPs block an EU exit?

Could the necessary legislation pass the Commons, given that a lot of MPs – all SNP and Lib Dems, nearly all Labour and many Conservatives – were in favour of staying? The referendum result is not legally binding – Parliament still has to pass the laws that will get Britain out of the 28 nation bloc, starting with the repeal of the 1972 European Communities Act.

The withdrawal agreement also has to be ratified by Parliament – the House of Lords and/or the Commons could vote against ratification, according to a House of Commons library report. In practice, Conservative MPs who voted to remain in the EU would be whipped to vote with the government. Any who defied the whip would have to face the wrath of voters at the next general election.

One scenario that could see the referendum result overturned, is if MPs forced a general election and a party campaigned on a promise to keep Britain in the EU, got elected and then claimed that the election mandate topped the referendum one. Two-thirds of MPs would have to vote for a general election to be held before the next scheduled one in 2020.

Will leaving the EU mean we don’t have to abide by the European Court of Human Rights?

The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in Strasbourg is not a European Union institution.

It was set up by the Council of Europe, which has 47 members including Russia and Ukraine. So quitting the EU will not exempt the UK from its decisions.

However, the UK government is committed to repealing the Human Rights Act which requires UK courts to treat the ECHR as setting legal precedents for the UK, in favour of a British Bill of Rights.

As part of that, the UK government is expected to announce measures that will boost the powers of courts in England and Wales to over-rule judgements handed down by the ECHR.

However, the EU has its own European Court of Justice, whose decisions are binding on EU institutions and member states.

Its rulings have sometimes caused controversy in Britain and supporters of a Brexit have called for immediate legislation to curb its powers.

Will the UK be able to rejoin the EU in the future?

BBC Europe editor Katya Adler says the UK would have to start from scratch with no rebate, and enter accession talks with the EU. Every member state would have to agree to the UK re-joining. But she says with elections looming elsewhere in Europe, other leaders might not be generous towards any UK demands. New members are required to adopt the euro as their currency, once they meet the relevant criteria, although the UK could try to negotiate an opt-out.

Who wanted the UK to leave the EU?

The UK Independence Party, which received nearly four million votes – 13% of those cast – in May’s general election, has campaigned for many years for Britain’s exit from the EU. They were joined in their call during the referendum campaign by about half the Conservative Party’s MPs, including Boris Johnson and five members of the then Cabinet. A handful of Labour MPs and Northern Ireland party the DUP were also in favour of leaving.

What were their reasons for wanting the UK to leave?

They said Britain was being held back by the EU, which they said imposed too many rules on business and charged billions of pounds a year in membership fees for little in return. They also cited sovereignty and democracy, and they wanted Britain to take back full control of its borders and reduce the number of people coming here to live and/or work.

One of the main principles of EU membership is “free movement”, which means you don’t need to get a visa to go and live in another EU country. The Leave campaign also objected to the idea of “ever closer union” between EU member states and what they see as moves towards the creation of a “United States of Europe”.

Who wanted the UK to stay in the EU?

Then Prime Minister David Cameron was the leading voice in the Remain campaign, after reaching an agreement with other European Union leaders that would have changed the terms of Britain’s membership had the country voted to stay in.

He said the deal would give Britain “special” status and help sort out some of the things British people said they didn’t like about the EU, like high levels of immigration – but critics said the deal would make little difference.

Sixteen members of Mr Cameron’s Cabinet, including the woman who would replace him as PM, Theresa May, also backed staying in. The Conservative Party was split on the issue and officially remained neutral in the campaign. The Labour Party, Scottish National Party, Plaid Cymru, the Green Party and the Liberal Democrats were all in favour of staying in.

US president Barack Obama also wanted Britain to remain in the EU, as did other EU nations such as France and Germany.

What were their reasons for wanting the UK to stay?

Those campaigning for Britain to stay in the EU said it gets a big boost from membership – it makes selling things to other EU countries easier and, they argued, the flow of immigrants, most of whom are young and keen to work, fuels economic growth and helps pay for public services.

They also said Britain’s status in the world would be damaged by leaving and that we are more secure as part of the 28 nation club, rather than going it alone.

What about businesses?

Big business – with a few exceptions – tended to be in favour of Britain staying in the EU because it makes it easier for them to move money, people and products around the world.

Given the crucial role of London as a financial centre, there’s interest in how many jobs may be lost to other hubs in the EU. Four of the biggest US banks have committed to helping maintain the City’s position. But HSBC will move up to 1,000 jobs to Paris, the BBC understands.

Some UK exporters say they’ve had increased orders or enquiries because of the fall in the value of the pound. Pest control firm Rentokil Initial says it could make £15m extra this year thanks to a weaker currency.

Others are less optimistic. Hilary Jones, a director at UK cosmetics firm Lush said the company was “terrified” about the economic impact. She added that while the firm’s Dorset factory would continue to produce goods for the UK market, products for the European market may be made at its new plant in Germany.

Image copyright REUTERS

Image copyright REUTERSWho led the rival sides in the campaign?

- Britain Stronger in Europe – the main cross-party group campaigning for Britain to remain in the EU was headed by former Marks and Spencer chairman Lord Rose. It was backed by key figures from the Conservative Party, including Prime Minister David Cameron and Chancellor George Osborne, most Labour MPs, including party leader Jeremy Corbyn and Alan Johnson, who ran the Labour In for Britain campaign, the Lib Dems, Plaid Cymru, the Alliance party and the SDLP in Northern Ireland, and the Green Party. Who funded the campaign: Britain Stronger in Europe raised £6.88m, boosted by two donations totalling £2.3m from the supermarket magnate and Labour peer Lord Sainsbury. Other prominent Remain donors included hedge fund manager David Harding (£750,000), businessman and Travelex founder Lloyd Dorfman (£500,000) and the Tower Limited Partnership (£500,000). Read a Who’s Who guide. Who else campaigned to remain: The SNP ran its own remain campaign in Scotland as it did not want to share a platform with the Conservatives. Several smaller groups also registered to campaign.

- Vote Leave – A cross-party campaign that has the backing of senior Conservatives such as Michael Gove and Boris Johnson plus a handful of Labour MPs, including Gisela Stuart and Graham Stringer, and UKIP’s Douglas Carswell and Suzanne Evans, and the DUP in Northern Ireland. Former Tory chancellor Lord Lawson and SDP founder Lord Owen were also involved. It had a string of affiliated groups such as Farmers for Britain, Muslims for Britain and Out and Proud, a gay anti-EU group, aimed at building support in different communities. Who funded the campaign: Vote Leave raised £2.78m. Its largest supporter was businessman Patrick Barbour, who gave £500,000. Former Conservative Party treasurer Peter Cruddas gave a £350,000 donation and construction mogul Terence Adams handed over £300,000. Read a Who’s Who guide. Who else campaigned to leave: UKIP leader Nigel Farage is not part of Vote Leave. His party ran its own campaign. The Trade Union and Socialist Coalition is also running its own out campaign. Several smaller groups also registered to campaign.

Will the EU still use English?

Yes, says BBC Europe editor Katya Adler. There will still be 27 other EU states in the bloc, and others wanting to join in the future, and the common language tends to be English – “much to France’s chagrin”, she says.

Will a Brexit harm product safety?

Probably not, is the answer. It would depend on whether or not the UK decided to get rid of current safety standards. Even if that happened any company wanting to export to the EU would have to comply with its safety rules, and it’s hard to imagine a company would want to produce two batches of the same products.

Thanks for sending in your questions. Here are a selection of them, and our answers:

Which MPs were for staying and which for leaving?

The good news for Edward, from Cambridge, who asked this question, is we have been working on exactly such a list. Click here for the latest version.

How much does the UK contribute to the EU and how much do we get in return?

In answer to this query from Nancy from Hornchurch – the UK is one of 10 member states who pay more into the EU budget than they get out, only France and Germany contribute more. In 2014/15, Poland was the largest beneficiary, followed by Hungary and Greece.

Image copyright THINKSTOCK

Image copyright THINKSTOCKThe UK also gets an annual rebate that was negotiated by Margaret Thatcher and money back, in the form of regional development grants and payments to farmers, which added up to £4.6bn in 2014/15. According to the latest Treasury figures, the UK’s net contribution for 2014/15 was £8.8bn – nearly double what it was in 2009/10.

The National Audit Office, using a different formula which takes into account EU money paid directly to private sector companies and universities to fund research, and measured over the EU’s financial year, shows the UK’s net contribution for 2014 was £5.7bn. Read more number crunching from Reality Check.

If I retire to Spain or another EU country will my healthcare costs still be covered?

David, from East Sussex, is worried about what will happen to his retirement plans. This is one of those issues where it is not possible to say definitively what would happen. At the moment, the large British expat community in Spain gets free access to Spanish GPs and their hospital treatment is paid for by the NHS. After they become permanent residents Spain pays for their hospital treatment. Similar arrangements are in place with other EU countries.

If Britain remains in the single market, or the European Economic Area as it is known, it might be able to continue with this arrangement, according to a House of Commons library research note. If Britain has to negotiate trade deals with individual member states, it may opt to continue paying for expats’ healthcare through the NHS or decide that they would have to cover their own costs if they continue to live abroad, if the country where they live declines to do so.

What will happen to protected species?

Dee, from Launceston, wanted to know what would happen to EU laws covering protected species such as bats in the event of Britain leaving the EU. The answer is that they would remain in place, initially at least. After the Leave vote, the government will probably review all EU-derived laws in the two years leading up to the official exit date to see which ones to keep or scrap.

The status of Special Areas of Conservation and Special Protection Areas, which are designated by the EU, would be reviewed to see what alternative protections could be applied. The same process would apply to European Protected Species legislation, which relate to bats and their habitats.

The government would want to avoid a legislative vacuum caused by the repeal of EU laws before new UK laws are in place – it would also continue to abide by other international agreements covering environmental protection.

How much money will the UK save through changes to migrant child benefits and welfare payments?

Martin, from Poole, in Dorset, wanted to know what taxpayers would have got back from the benefit curbs negotiated by David Cameron in Brussels. We don’t exactly know because the details were never worked out. HM Revenue and Customs suggested about 20,000 EU nationals receive child benefit payments in respect of 34,000 children in their country of origin at an estimated cost of about £30m.

But the total saving would have been significantly less than that because Mr Cameron did not get the blanket ban he wanted. Instead, payments would have been linked to the cost of living in the countries where the children live. David Cameron said as many as 40% of EU migrant families who come to Britain could lose an average of £6,000 a year of in-work benefits when his “emergency brake” was applied. The DWP estimated between 128,700 and 155,100 people would be affected. But the cuts would have been phased in. New arrivals would not have got tax credits and other in-work benefits straight away but would have gradually gained access to them over a four year period at a rate that had not been decided. The plan will never be implemented now.

Will we be barred from the Eurovision Song Contest?

Image copyright AP

Image copyright APSophie from Peterborough, who asks the question, need not worry. We have consulted Alasdair Rendall, president of the UK Eurovision fan club, who says: “All participating countries must be a member of the European Broadcasting Union. The EBU – which is totally independent of the EU – includes countries both inside and outside of the EU, and also includes countries such as Israel that are outside of Europe. Indeed the UK started participating in the Eurovision Song Contest in 1957, 16 years before joining the then EEC.”

Has Brexit made house prices fall?

Image copyright PA

Image copyright PAAs with most elements of the UK economy, not enough solid data has been published yet to accurately conclude the Brexit effect on house prices. Industry figures have pointed to “uncertainty” among buyers and sellers that could potentially change the housing market.

So far, the most significant research has come from the respected Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, which has published the conclusions of a survey of its members. This primarily records sentiment among surveyors.

It found that house prices are expected to fall across the UK in the three months after the referendum vote. However, the dip in prices is only expected to persist over the 12 months from June in London and East Anglia, surveyors predict.

House prices were already slowing in central London, owing to the fall-out from changes to stamp duty rules in April.

Separate figures from property portal Rightmove suggested the average asking price of houses coming on to the market in England and Wales fell by 0.9%, or £2,647, in July compared with June. It said that agents had reported very few sales had fallen through as a result of the vote.

Many potential first-time buyers would welcome a fall in house prices, with ownership among the young falling owing to affordability concerns. Investors in property, or those who have paid off a mortgage and hope to leave homes as inheritance would be unhappy with a long-term reduction in value.

What is the ‘red tape’ that opponents of the EU complain about?

Ged, from Liverpool, suspects “red tape” is a euphemism for employment rights and environmental protection. According to the Open Europe think tank, four of the top five most costly EU regulations are either employment or environment-related. The UK renewable energy strategy, which the think-tank says costs £4.7bn a year, tops the list. The working time directive (£4.2bn a year) – which limits the working week to 48 hours – and the temporary agency workers directive (£2.1bn a year), giving temporary staff many of the same rights as permanent ones – are also on the list.

There is nothing to stop a future UK government reproducing these regulations in British law following the decision to leave the EU. And the costs of so-called “red tape” will not necessarily disappear overnight – if Britain opted to follow the “Norway model” and remained in the European Economic Area most of the EU-derived laws would remain in place.

Will Britain be party to the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership?

Ste, in Bolton, asked about this. The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership – or TTIP – currently under negotiation between the EU and United States will create the biggest free trade area the world has ever seen.

Cheerleaders for TTIP, including former PM David Cameron, believe it could make American imports cheaper and boost British exports to the US to the tune of £10bn a year.

But many on the left, including Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, fear it will shift more power to multinational corporations, undermine public services, wreck food standards and threaten basic rights.

Quitting the EU means the UK will not be part of TTIP. It will have negotiate its own trade deal with the US.

What impact will leaving the EU have on the NHS?

Paddy, from Widnes, wanted to know how leaving the EU will affect the number of doctors we have and impact the NHS.

This became an issue in the referendum debate after the Leave campaign claimed the money Britain sends to the EU, which it claims is £350m a week, could be spent on the NHS instead. The BBC’s Reality Check team looked into this claim.

Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt warned that leaving the EU would lead to budget cuts and an exodus of overseas doctors and nurses. The Leave campaign dismissed his intervention as “scaremongering” and insisted that EU membership fees could be spent on domestic services like the NHS.

Former Labour health secretary Lord Owen has said that because of TTIP (see answer above) the only way to protect the NHS from further privatisation was to get out of the EU.

Source: BBC.com

Excellent Article, cleared lot’s of questions up.

This is more of an educating article on Brexit…good work

Must say this a COMPLETE article on Brexit